By July 1758, the British recaptured the Louisbourg fort, winning control over the St. Lawrence river entrance, and thus were in a position to cut off French supplies.

The Iroquois soon joined the British, wishing to be on the side of the winners. By 1760, the British had won Montreal.

There was a peace negotiated in Paris in 1763, in which France gave away its claims to north American territories (all!) to Britain and Spain. Before, the French had claimed a huge swath of territory that from North-east Canada down through the Great Lakes all the way through Mexico; after the Treaty it was just England down through the new frontiers of New Spain, which also got some territory from the French. (Note: While native communities inhabited these lands and also claimed them as their own, neither the French, the Spanish, nor the British considered the claims of native peoples as binding or even legitimate.)

Effect on the Indians

The Indians lost out hugely in this war, since they lost the productive rivalry between France and Britain, which had until then given them leverage in negotiating with either party (if we don’t like your deal, we’ll just go to the other side). Now, the threat of allying with the other side no longer existed. In the eyes of most colonial pioneers, entrepreneurs, settlers, and wealthy land speculators, Indians were merely an obstacle standing in between them and a vast set of resources and wealth. (See our class primary sources on Native Americans here.)

Indians unite!–Neolin and Pontiac

Neolin, a religious prophet, was prescient about the fact that the Indians only chance to  resist the colonial onslaught at this point was for all of its tribes to unite in opposing the continued European invasion of native territory. Neolin preached that he had been instructed by the Master of Life, in a vision, that Indians should reject European technology and commerce, and return instead to the old ways. While native societies tended to regard themselves as many different peoples, Neolin taught that Indians shared a common identity and should unit against Europeans in ejecting them from Indian territories.

resist the colonial onslaught at this point was for all of its tribes to unite in opposing the continued European invasion of native territory. Neolin preached that he had been instructed by the Master of Life, in a vision, that Indians should reject European technology and commerce, and return instead to the old ways. While native societies tended to regard themselves as many different peoples, Neolin taught that Indians shared a common identity and should unit against Europeans in ejecting them from Indian territories.

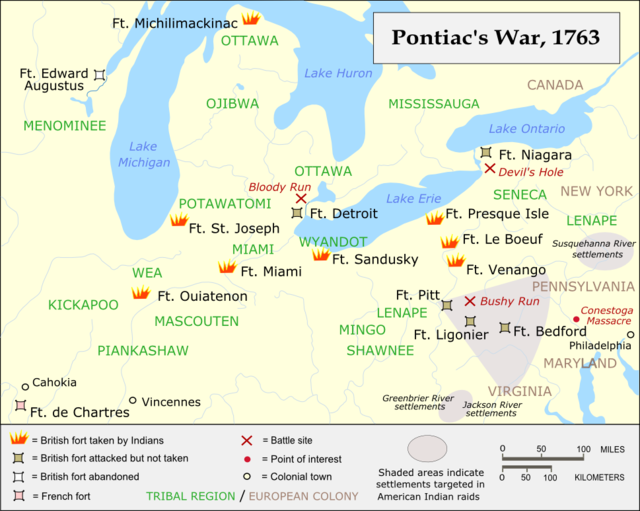

Pontiac, a chief of the Ottawa village near Detroit, took Neolin’s advice to heart. He forged an unprecedented alliance among Hurons, Chippewas, Potawatomis, Delawares, Shawnees, and Mingoes, and in spring 1763 attacked the British outposts, totally overcoming all of them in the region but Detroit. The Virginia and Pennsylvania frontiers were also raided, and two thousand settlers captured or killed during the onslaught. Thousands of settlers fled the frontier. This came to be called Pontiac’s Uprising. Colonial militiamen would respond in late summer, and several substantial victories victories. It would take three years for the conflict to die down, with a treaty finally being signed.

Pontiac’s speeches in 1762 and 1763 echoes the Response of a Micmac Indian, which we read in class. Here is an excerpt:

Englishmen, although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods, and mountains were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance; and we will part with them to none. Your nation supposes that we, like the white people, cannot live without bread and pork and beef! But you ought to know that He, the Great Spirit and Master of Life, has provided food for us in these spacious lakes, and on these woody mountains.

[The Master of Life said to Neolin:] I am the Maker of heaven and earth, the trees, lakes, rivers, and all else. I am the Maker of all mankind; and because I love you, you must do my will. The land on which you live I have made for you and not for others. […] You have bought guns, knives, kettles, and blankets from the white man until you can no longer do without them; and what is worse, you have drunk the poison firewater, which turns you into fools. Fling all these things away; live as your wise forefathers did before you. And as for these English,–these dogs dressed in red, who have come to rob you of your hunting-grounds, and drive away the game,–you must lift the hatchet against them (Foner, 169).

In Britain, news of this upheaval only strengthened British resolve to clamp down on policies limiting frontier expansion. Resentment among the colonists and hatred of native peoples flourished.

The British had no desire to actually have to govern such an unruly territory as the frontier. Instead, they issued in 1763 a Proclamation regarding settlement, declaring that the territory from the Atlantic to the Appalachians was open for settling business–but the territory to the west of that needed to be left to the Indians. The British motivation here was simply to avoid border conflicts. But the settlers totally ignored the Proclamation, and considered the border open for business, with both pioneers and land speculators zealously pursuing their interests. George Washington was himself a land speculator at the time, and ordered his agent to buy up as much Indian land as possible.

I really don’t like what the French, British and Spanish countries are doing. There are acting like the native Americans have no rights at all to the land they have been living in since they crossed the strait! Just because those countries have the big guns and the large armies doesn’t mean that they can do things like this. They acted like the land was a field with animals in it with no civilization! Maybe it isn’t the same type of civilization, but still, THEY ARE PEOPLE!!!

LikeLike